“Would things be easier if there was a right way? Honey there is no right way.”

- Someone New, Hozier

I remember the first time I watched Indecent Proposal, an erotic drama that captivated me both with it’s premise and execution. I was a preteen, crowded around a box television in my uncle’s den hyper vigilant of every sound in the house, lest he catch me in the act. I couldn’t gauge all the reasons he’d disapprove of the film but I knew the central plot would be one of them. It’s simple really: high school sweethearts turned spouses down on their luck head to Vegas hoping to turn it all around, and the opportunity to do so arises with John Gage, a billionaire so enraptured with Diana’s aloofness towards him, that he makes a proposition only men used to getting what they want would. If you allow me one night with you, I’ll give you a million dollars.

It’s the civilian’s1 imagination of a hooker’s dream really (much like Pretty Woman was), and they’re not that far off.

It’s angsty and sexy and uncommitted in it’s cynicism about love. I found myself revisiting it over the years for reasons I couldn’t quite place until reading the Robert Ebert review,

“Indecent Proposal” is in a very old tradition, in which love is put to the test of need and desire and triumphs in the end, although not without a great many moments when it seems quite willing to cave in to passion.2

The story though assuming the traditional 3 act structure can be cleaved into halves, before the proposal and after. In many ways, partnership can be catalogued this way as well.

A request. Rumination. A decision. And how one lives with it.

The most human thing about us is our propensity to wonder, to continue to asks questions with an answer already tucked in our pocket. Since the dawn of time, sentient beings have been needlessly seeking: comfort, security, food, community, what makes a cold night pass easier and a hot day more bearable. Despite knowing this about ourselves, an expectation arises in society, one that asks we suspend every inch of curiosity our species demands to prove our love is earnest and true. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think this was the function of love, or really, marriage for that matter.

Generally speaking, at the core of every great love story and its auxiliary heartbreaks is the question of marriage. Do we do it? Are we doing it well? Should we have done it at all? Considering how we discuss marriage currently, you’d think love is and has always been its primary motivating factor which lends a rather ahistorical account to it’s hows and whys. Though many marry for love today, it wasn’t always like this actually, it just started being like this. Marriage is sociopolitical and based on its origins, designed to assert ownership over property which were women and children post agricultural revolution. There’s functional ownership baked into marriage and was meant to reaffirm power structures that punished a refusal to conform, it’s the very reason marriage eligibility exists at all.

And despite recent history suggesting otherwise, marriage never lost its bite. No-fault divorce3 is younger than my parents. Women’s ability to independently own credit cards and access lines of credit4 is even younger than that. Marital rape wasn’t recognized as an assault and thus crime until 1993 in the US5. The specter of violence within the marital apparatus has been taken out of public view, namely due to marriage’s rebrand as a love commitment, we can thank marketers for that.

In media exploring marriages, we’re inundated with the idea that marriage as an exercise of love is superior because it sands down the rough edges of its practical function. Like sleight of hand performed by a magician, we’re meant to think only of its benefits and perhaps more importantly, believe the benefits capable of excising ourselves of further meditation on the decision, and what we’ve let go of to make it. Love is damn near incapable of being partitioned from marriage because marriage is considered the principle expression of love. To question your marriage, is to question the sanctity of love itself.

The central tension in all erotic and romantic dramas come from our protagonists deviating from their unquestioning. As a society, we can be painfully idealistic about love and it’s power. It’s meant to be opaque in its uncertainties and very romantic about its virtues. The perfect escape. A cushy landing in an otherwise cruel and inconsiderate world so what does it say when even long time companionship finds itself under examination still?

The rom-com doesn’t answer these questions, but rather leans in to the opposing view, that true love requires no questions, the answer is your person.

Screenwriting couple, Celine Song and Justin Kuritzkes took film by storm last year when Past Lives & Challengers released barely two months apart asking similar questions about marriage, love, desire and the potential of connections. The films couldn’t be more different in their approach and even in how they attempt to answer the question but the questioning itself, by a married couple no less, led to public deliberations about the quality of their marriage and whether their respective film plots were meant to indicate troubled waters.

The nosiness of the public is always to be expected, especially in the social media age which has democratized voyeurism and corroded social etiquette in relation to personal privacy. The boundaries are porous and the desire to pry into the couples personal life is in part promoted by Song’s affirmation that Past Lives is a work of auto fiction. She too is a Korean-Canadian-American writer who passed on her childhood sweetheart to settle in New York with her white Jewish-American writer husband. It was all the fuel people needed to run with the idea that these movies are functioning as couple’s therapy or perhaps a confession by the respective screenwriters. Multiple publications wrote about it, some demanding the public drop the fixation, while others fed it.

Stop Looking for the Challengers/Past Lives Third - Vulture

Challengers and Past Lives are engaged in a secret, sexy conversation - Decider

Through tastefully placed flashbacks and double speak in the current timelines, we see six people (between both films) reconcile with a shared and distant past, restless with uncertainty. It’s the age old trope rom-coms choose to cart around unabashedly: the first love v. the (presumed to be) last. While these characters reflect on the role they’ve played in each other’s lives, moments that would otherwise feel pedestrian are elevated by a clock, because questions demand answers, love demands answers.

In Past Lives, Nora Moon née Na Young, is compelled to consider the decisions that led her to New York and subsequently, her husband when Hae Sung Jung, her childhood sweetheart finally makes it across the ocean to see her. Their reunion is awkward and stilted yet full of affection, the years weathered them a bit, sure but the care is evident. Even if they don’t know how to feel about seeing each other after all this time, they’re indeed, feeling, deeply.

Across the duration of a nearly 2 hour runtime we witness the emotional waxing and waning of Nora and Hae Sung attempting to ease all the confusion around their connection while toeing the lines of propriety because Nora is married. They demand little of each other aside from honesty and even that is colored by nearly finished statements, weighted glances and double speak. Two decades of history and what ifs are further punctuated by Arthur, Nora’s husband’s presence both literally and metaphorically across the film.

He does all the right things. He’s kind and understanding about Nora’s desire to see Hae Sung and experience him corporeally for the first time in their adult lives and is ever hospitable when he meets him. Despite this, he can’t help but feel inadequate compared to her first love; they share more than history, they share a world, a language and culture. Nora is known to Hae Sung in ways Arthur never will experience, it’s what breeds his anxieties about their renewed connection. He’ll always have met Nora after she became Nora, whereas Hae Sung got to experience all iterations, the girl that was Na Young and the woman that is Nora Moon.

Nora spends an entire day with Hae Sung where they attempt to enjoy each other just enough for their reunion to be worth it but less than anything that can be read as romantic intent. They ignore the longing only they (and Arthur by the end of the movie) can see because choices were made, and they feel comfortable standing by them.

The film’s climax isn’t a big bang, Hae Sung and Arthur don’t come to blows. Instead the three of them grab dinner, enjoy each other’s company in the liminal space of the two paths Nora’s life could have taken and with who. And with some liquid courage, the curtains are parted and the childhood sweethearts have a beautifully transparent conversation in Korean, the language they learned to love each other in.

Arthur, though present for this conversation, respects its privacy. He scrolls his phone as his wife speaks to what could have been the love of her life in their native tongue and pretends it doesn’t stir complicated and undeniably wounded feelings within him. Though we often see discussions about fate and soulmates, it’s entirely possible that our lives, our love lives most of all, is driven solely by personal choice. Is that not where the nail biting comes from? If one chooses to stand by their decisions, then they’re admitting there were decisions to make, that this all encompassing love didn’t spawn passively but rather through deliberate effort to know and grow with another.

In the end, Nora’s lucky, she gets to gaze between the two great loves of her life and make peace with her path. The question: who’d I be if this didn’t happen? who’d I be if it did? becomes obsolete because this moment, these connections, her marriage are the answer, there’s wisdom in that.

Challengers takes an alternative view. If Past Lives is stripped down and quietly meditative, Challengers is brash and unencumbered in its prodding. In Justin Kuritzkes world, tennis provides the backdrop for relationships that span nearly half of these characters lifetimes as well as a medium to talk when they find themselves unable, or realistically, reluctant to. Everything’s about tennis, so nothing’s about tennis and the matches we witness on screen are the closest our triad get to authentic expressions of their frustrations, hopes and dreams.

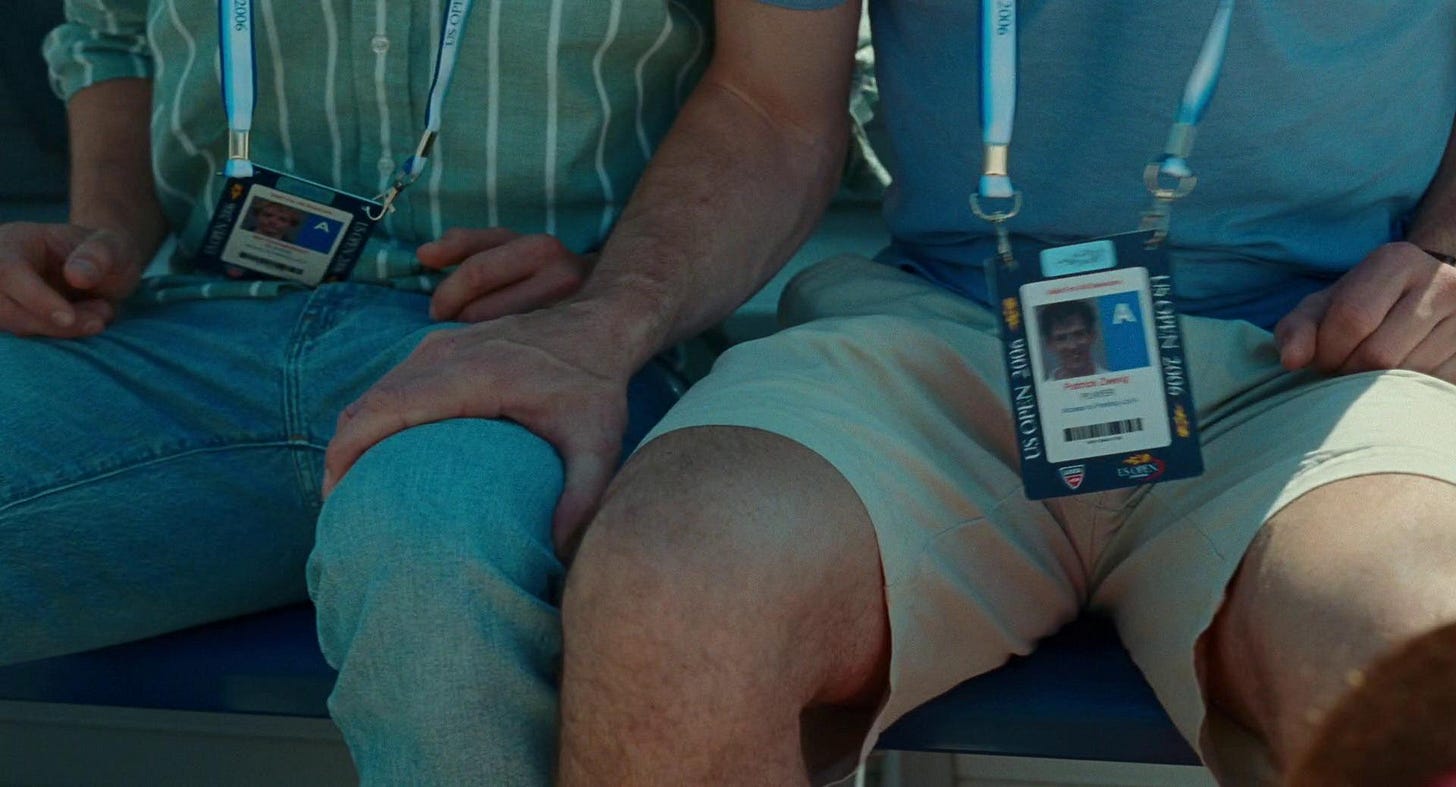

Despite our film beginning well into these character’s mess, the love story ultimately commences before either boy meets Tashi. Art and Patrick, teen tennis prodigies had spent years together as best friends, shrouding homoerotic longing for each other in anything capable of being an intermediary.

Tashi was inheriting a love story, not starting one. Tennis being a vehicle to confront their desire is made especially fascinating by her inclusion because of what the sport, and by virtue the men, grow to mean to Tashi. Art and Patrick are white boys with affluent legacies couching them in security whereas Tashi comes from a working class family, and is Black in one of the whitest sports in the world. Tennis is a game for the boys but for Tashi, it’s her lifeline— her chance at a dazzling and spectacular existence typically reserved for the Elite. For Tashi, loving tennis isn’t a happy accident but rather compulsory in order to see to the mobility and adoration she seeks. In a lot of ways, everyone in her life remains inferior to the sport; any partner of hers is in a love triangle with tennis and the only way out, is through winning.

Tashi has it all: the technicality and grace we saw in Art, accompanied with the intuitive raw power and tenacity we saw in Patrick. She’s the best of the both of them, she’s the best tennis has to offer. The immediate draw towards her is as much about her elevated game as it is her beauty. When the boys watch her play, get to experience her objectively for the last time, it’s ripe with wonder and an electricity they refuse to name but you can feel. They want Tashi, a female counterpart and perfect mix of their respective traits, meaning they also want each other.

When our actual romance begins to transpire on screen, it’s with all three of our characters, the sectioning off will come later. Tennis ultimately determines who has access to Tashi and with so many factors crowded into a room (or on double beds shoved together at a shitty hotel in Flushing), conflict is bound to happen. Unlike Past Lives, Challengers doesn’t ask us to wonder about the depth of romantic feelings between our throuple, but rather the depth of their devotion to the sport responsible for leading them to each other.

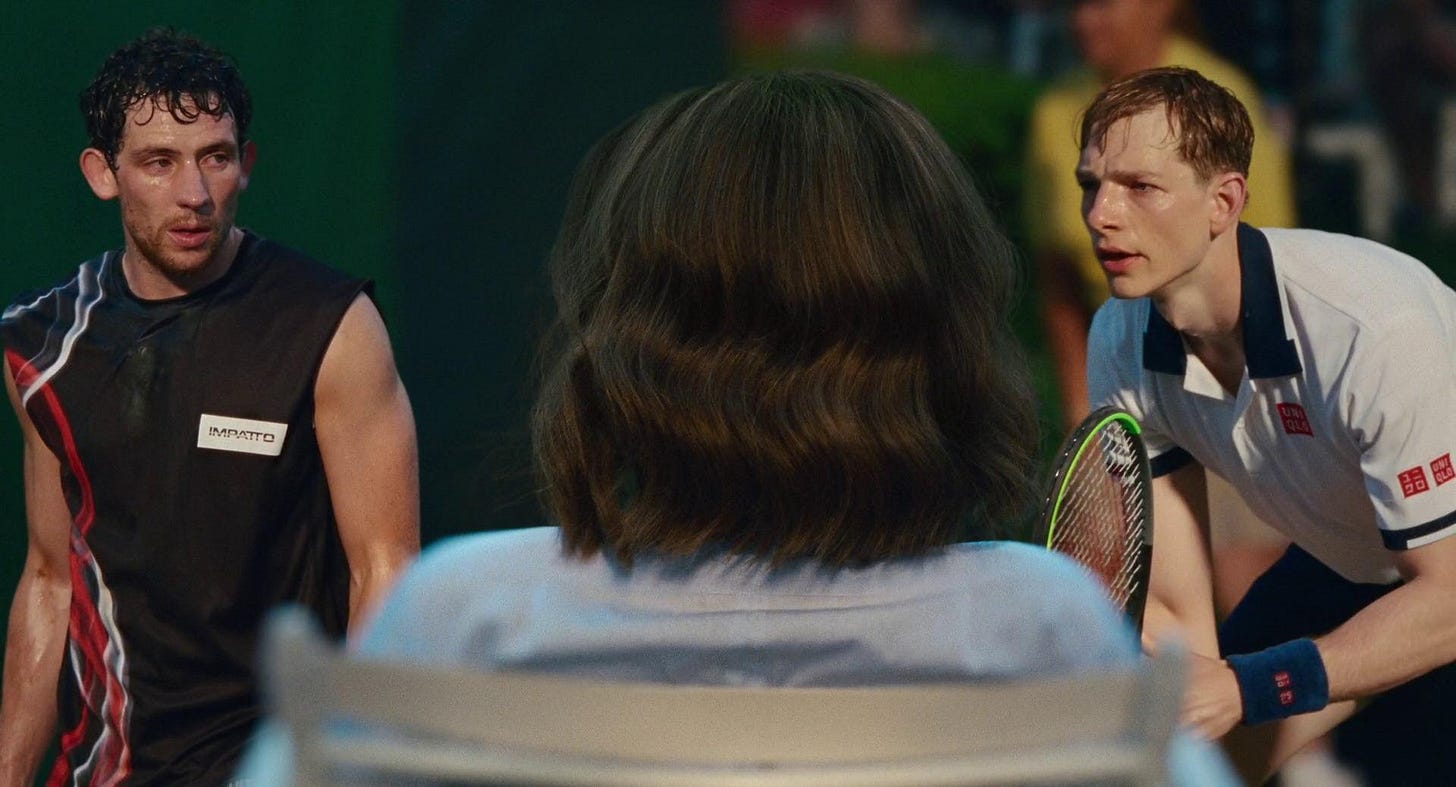

The vulnerable moments of their shared pasts is interspersed with the 2019 Challenger Final, where Art and Patrick, once best friends, now 12 years estranged, get to hash their mess out on the court while a hungry public and even hungrier Tashi watch. The question: what could have been? is entertained by all of our protagonists respectively because they all lost something shortly after finding each other. Tashi arguably most of all when a devastating freak injury (caused by Art’s meddling to be clear) ends her career before she could even go pro.

So regarding the romance, the question isn’t so much: which man is better for me? but actually, are these men a reflection of all I’d have amounted to?

Tashi, by way of her relationship with these men gets to experience both outcomes, and ponder them in equal measure though she only has control over one, the life and thus career she chose with Art. She’s forever calm and collected in public, she’d never give away her personal power or the leverage her casual aloofness affords her yet even still, the cracks in her veneer deepen as the challenger progresses.

This tournament matters far more than she’d ever admit, we become aware a little over half way through the film that a big decision will proceed this season. Either Art wins and goes on to complete his career Grand Slam and she finds contentment (hopefully) in the career she nurtured or Patrick wins and Art is devastated, using the embarrassment of the loss to rid him of trying to win the US Open, paving the way for his retirement. As Patrick tells Tashi in the alleyway,

The only reason Tashi can love Art is because he gave her what Patrick never could, total control over his career, his life’s trajectory and legacy. He’s a devotee of Tashi’s, kneeling in supplication to her heart’s desire except, it’s not enough. Art’s a good tennis player, a great one even, but he’s no Tashi. Tashi would have completed her career grand slam by now. Tashi would have been the face of all the brands. Tashi would have been something indescribable and rare. Instead, she’s the wife and coach of a man who’s only ever almost enough. If this pains Art, it mortally wounds Tashi.

It’s the core of her frustrations with Patrick, if there was a man she could have molded in her image, it would have been him but he had too much hubris and too little drive to sustain. To mourn the strain in their relationship (I hesitate to say end considering she fucks him on the low), means accepting she’s as much of a has-been or could-have-been as him. If there’s a version of Tashi that went on to become the GOAT because she was never injured, then there’s also a version of Tashi that went pro and fumbled her way through a career that could only be described as unsatisfactory.

The feelings she has for Patrick and Art are secondary, they serve as a vector for the actual love of her life, tennis. If Nora belongs only to herself, making her content with her decisions in life, then Tashi belongs to the court, to the highs and lows of tennis. And she doesn’t know who she is without tennis and gives us no indication she wants to find out.

Unlike Past Lives, our resolution doesn’t come from sincere conversation earmarked by tender feelings. Challengers takes its conflict to the place it began, the tennis court. After Patrick plays his hand (signalling to Art that he & Tashi fucked), they decide to settle the score once and for all. It’s a punishing volley that closes the gap, literally and figuratively in our throuples relationship and as Tashi tries to follow along the sidelines, her presence cocoons the men like a shawl. For once, in twelve years, they’re experiencing the relationship that is tennis together and it only took a random draw, deceit and infidelity to do so.

These love stories, split over decades and continents all punctuated by life altering events outside of our characters control, allow space to ask hard questions we’re told cease to exist when true love occurs.

Was there another option for me, for us? Is the merit of love and desire bound to its profound uniqueness? Does the sincerity of our connections hinge on their irreplicable nature? Where does the harm lie, in asking the question or admitting you have one?

Neither Song nor Kuritzkes answer this with a pretty bow, but they questioned it, which in a lot of ways is enough.

In the rom-com, it’s almost guaranteed that in order to prove fealty to your one true love, you must make a spectacle of your past connections. The lead is made to disavow all the love they’ve stumbled through prior to ending up here, as proof nothing could ever amount to this. Personally, I find love too dynamic to contain to my current partner(s), even when I think I want to experience them forever. Our lives are cumulative, who’s to say we’d be capable of finding true love if we hadn’t micro dosed it along the way?

Diana, Nora and Tashi dared to wonder and refused to apologize for it. The men who loved them fell in love with women who question and it would be a disservice to them to expect anything different. Whether a million dollars, In-Yun or a career grand slam, we wouldn’t find ourselves dreaming of what isn’t possible and the ability to visit that place, caress its edges fondly, then come back to the life we choose, might be the most romantic tale of all.

How sex workers refer to non-sex workers

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/indecent-proposal-1993

https://www.cnn.com/2023/11/27/us/no-fault-divorce-explained-history-wellness-cec

https://womenshistory.si.edu/blog/voices-independence-four-oral-histories-about-building-womens-economic-power

https://vawnet.org/material/marital-rape-new-research-and-directions

I need to read this a couple more times and do some pondering before being able to formulate a proper comment but I just wanted to say your writing is like oil for the cogs of my brain. I think you're so so brilliant and it's a pleasure to be coaxed into new ideas and ways of thinking by your work. Thank you!!! Life is infinitely more interesting when we pick apart what is assumed to be sacred and stay blasphemously critical.

I read this before I slept and might read it again because it was a lovely experience. Have I watched the movies you talked about? No. But you just have this way of carrying someone with you as you talk about the characters, their dynamics, love. It's like we were breaking down the movies together and the way they mirrored each other but we're somehow really different. Again, a beautiful, beautiful read.